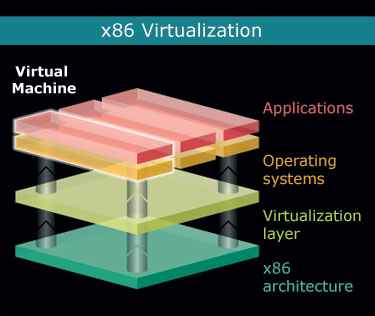

Many of us have heard about hardware virtualization, but as far as I can see there is still a lot of confusion around this term and surrounding technologies, so today I’ve decided to give a really quick intro. Some time in the future, I’ll probably cover this topic in detail.

What is hardware virtualization?

First of all, let’s agree – in most conversations, when people say hardware virtualization, they really mean hardware assisted virtualization. If you learn to use the correct (latter) form of this term, it will immediately start making more sense.

Hardware assisted virtualization is a common name for two independent but very similar technologies by Intel and AMD which are aimed to improve the processor performance for common virtualization challenges like translating instructions and memory addresses.

AMD virtualization is called AMD-V, and Intel virtualization is known as Intel VT or IVT.

Here’s what AMD has to say about it’s AMD-V technology:

AMD-V™ technology enables processor-optimized virtualization, for a more efficient implementation of virtualization environments that can help you to support more users, more transactions and more resource intensive applications in a virtual environment.

And that’s what Intel says about Intel VT:

With support from the processor, chipset, BIOS, and enabling software, Intel VT improves traditional software-based virtualization. Taking advantage of offloading workloads to system hardware, these integrated features enable virtualization software to provide more streamlined software stacks and “near native” performance characteristics.

Essentially, hardware assisted virtualization means that processors which support it will be more optimized for managing virtual environments, but only if you run a virtualization software which supports such a hardware assistance.

Common myths and confusions about hardware virtualization

There’s a number of ways people misunderstand the technologies behind hardware assisted virtualization, and I’d like to list just a few of the really common ones.

Misunderstanding #1: full virtualization capability built into hardware

People think: Hardware virtualization means your PC has a full virtualization capability built into hardware – you can install a few operating systems and run them in parallel with a special switch on the PC case or a special key on the keyboard for switching between them.

In reality: While it seems like PC-based desktop virtualization technologies head this way, hardware assisted virtualization is not quite there yet. You don’t have a special button on your PC case for switching VMs, and there isn’t a key on your keyboard to do it neither. Most importantly, any kind of virtualization is only possible with the help of hypervisor – a virtualization software which will assist you in creating and managing VMs.

Misunderstanding #2: incredible performance boost with hardware virtualization

People think: Hardware virtualization means your virtual machines will run in parallel at the native speed of your CPUs, so if you have 3 VMs running on a 3Ghz system, each one of them will be working at full 3Ghz speed thanks to AMD-V or Intel VT.

In reality: even with hardware assisted virtualization, your VMs will still be sharing the computational power of your CPUs. So if your CPU is capable of 3Ghz, that’s all your VMs will have access to. It will be up to you to specify how exactly the CPU resources will be shared between VMs through the software (different software solutions offer you various flexibility at this level).

I sense that the common misunderstanding here is that hardware virtualization is a technology similar to multi-core support, which somehow makes one advanced CPU perform as good as 2 or 4 regular ones. This is not the case.

Hardware assisted virtualization optimizes a subset of processor’s functionality, so it makes sense to use it with appropriate software for virtualizing environments, but apart from this a CPU with AMD-V or Intel VT support is still a standard processor which will obey all the common laws of its design features – you will not get more cores or threads than your CPU already has.

Misunderstanding #3: an improvement for every virtualization solution

People think: Every virtualization solution available on the market will benefit from hardware assisted virtualization.

In reality: there’s quite a few solutions which do not use hardware assistance for their virtualization, and therefore won’t really benefit if your CPUs support it. To a surprise of many, the reason such solutions don’t support hardware virtualization is not because they lag behind the rest of the crowd in accepting and supporting new technologies: they simply want to stay flexible and not limit their deployment to the most recent systems.

Bochs and VirtualBox are two good examples of a different approach to virtualization – the binary translation. What this means is that they fully emulate and implement all the x86 instructions in their software, using only standard instructions. While their performance would probably benefit from hardware assisted virtualization support, these solutions enjoy a far better flexibility as they don’t require you to have AMD-V or Intel VT support in order to run. In fact, Bochs doesn’t even need you to have an x86 hardware to run and successfully emulate x86 virtual machines! Sure, it can be slow – but that’s to do with the hardware you’re using – so if you have fast enough CPUs, you will even be able to run Windows on SPARC system.

Final words

That’s it for today. Hopefully this article has helped you understand what hardware assisted virtualization is and, more importantly, what it isn’t. Do come back again as I’ll be expanding this topic in my future posts.

If you notice any discrepancies or feel like this article should be expanded, can you please let me know? I’m not an expect in desktop virtualization (yet) and still learn something new every day, so I’ll be delighted to hear your opinion on the subject.

See Also